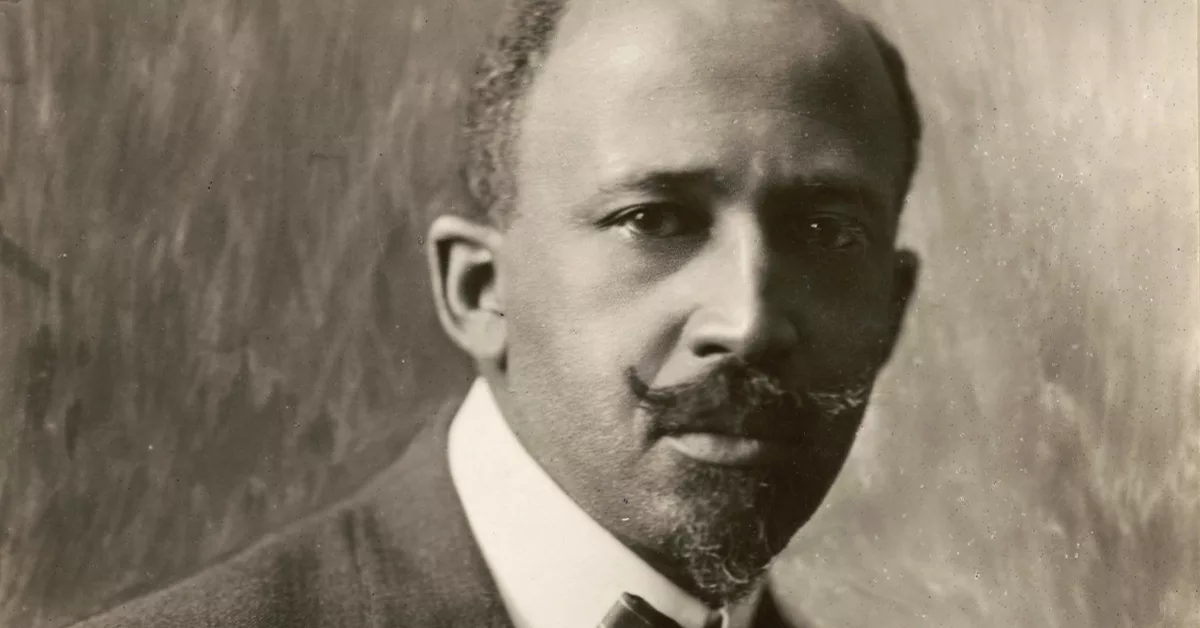

Only 10 short months ago, the Trump administration declared “diversity, equity and inclusion” (DEI) initiatives to be illegal and immoral, radical and wasteful. Now PBS is racing to complete a documentary about civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois, after losing funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities in April and learning that the administration would “cease federal funding” to PBS and NPR in May. Despite these setbacks, they forged ahead with “W. E. B. Du Bois: Rebel with a Cause,” which is slated to air next year as part of their “American Masters” series — provided they can raise $100,000 to complete post-production.

Lee-based nonprofit Multicultural Bridge will host a fundraising event in Great Barrington on Saturday, Dec. 6. Born in 1868, Du Bois was raised in Great Barrington, said Eleanor Levine, an associate producer of the documentary.

“They really supported him from a young age,” said Levine, who was born in Amherst who now lives in Holyoke. “He was the class valedictorian, and they could tell he had talent. His church congregation helped fundraise for him to go to college. I really don’t think he would have had the opportunity [otherwise].”

Levine noted that Du Bois’ father was absent and his mother died while he was in high school. “The community really showed up for him and they’re still showing up for him,” she said.

CONTRIBUTED

Levine also said that the controversy around Du Bois’s adoption of communism late in life is addressed head-on in the film, which is directed by Rita Coburn, who has produced several documentaries in the award-winning “American Masters” series. Du Bois, who cofounded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), was eventually blacklisted for his politics. He was shut out both globally and locally, which may explain why the 2020 renaming of Monument Valley Regional Middle School in Great Barrington to the W. E. B. Du Bois Regional Middle School took 15 years to realize. Earlier this year, a statue of Du Bois was unveiled in his hometown at the Mason Public Library.

In the film, Aldon Morris, the Leon Forrest Emeritus Professor of Sociology and African American Studies at Northwestern University, explained that Du Bois ultimately had good intentions.

“Du Bois actually thought that socialism was going to win out and usher in a new era of human emancipation,” he told PBS. “We can say in hindsight that there was some naivete on the part of Du Bois. There were times where he was uncritical of communism in terms of how it was practiced. The main thing is to understand that Du Bois wanted to embrace any system that he thought would liberate humankind.”

A scholar in his own right, Du Bois published 17 books and countless magazine articles during his 95 years on Earth. His seminal work was “The Souls of Black Folk,” published in 1903, in which he explored being “a problem,” rather than a person.

“I was a little thing, away up in the hills of New England, where the dark Housatonic winds between Hoosac and Taghkanic to the sea,” he wrote, recalling being rejected by a girl in grade school because she didn’t like the look of him. “Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from the others … Such a double life, with double thoughts, double duties, and double social classes, must give rise to double words and double ideals, and tempt the mind to pretense or revolt, to hypocrisy or radicalism.”

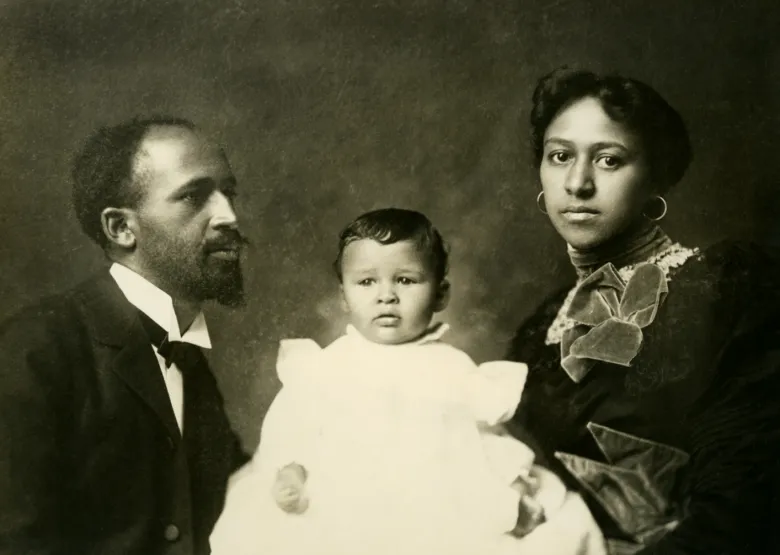

Throughout his lifetime, Du Bois shined a light on structural racism. The documentary focuses on the “vast scope” of his work as well as his “complicated home life,” said Levine. The production team did a four-hour preliminary interview with former Berkshires resident David Levering Lewis, who was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his biographies of Du Bois in 1993 and 2000. Then they interviewed experts on distinct parts of his life, and brought in three Academy Award-winning actors to read his words on-screen.

CONTRIBUTED

PBS got the majority of their archival material from the W. E. B. Du Bois Center at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The center’s director, Whitney Battle-Baptiste, who is also a professor in the Anthropology Department, helped coordinate access behind-the-scenes.

“It made me appreciate the power of archives and the importance of making things accessible, which was part of the motivation of [Du Bois’s second wife] Shirley Graham Du Bois, who sold the [Du Bois] collection to UMass and Harvard,” said Battle-Baptiste. She said that the digital catalogue “is probably one of the most clicked upon resources that is used on a scholarly level. It’s used a lot, which is good, because it continues his legacy.”

Battle-Baptiste also noted that documentaries provide multiple audiences with visuals of important documents, which humanizes people who may be idolized or misunderstood.

“You can see when scholars crossed things out, when they questioned their own process,” she said, adding that she’s excited to see the finished product and show it to her students.

At the Dec. 6 fundraiser, PBS will unveil some sneak previews of the documentary. Coburn, the director, and Fredara Hadley, an ethnomusicology professor at Juilliard, will be on hand for a Q&A. Donations can be made at documentaries.org/films/w-e-b-dubois/. The Better Angel Society will match any contributions of $5,000 or more until the end of the year.

Levine hopes that young people in particular take something away from the film.

“I have to admit I can’t believe we didn’t learn about him in high school,” she said. “[His story is] about even more than the span of his lifetime, because he was looking into the past and looking into the future.”